Common Logical Fallacies

1. Confirmation Bias / Cherry-Picking

What it is

- Seeking evidence that confirms existing beliefs

- Ignoring contradictory evidence

- Selectively reporting favorable results

Example

Person: "Vaccines cause autism!"

Evidence: 1 study (retracted, fraudulent) says yes

100+ studies say no

Action: Cites the 1 study, ignores the 100+

Why it’s bad

- Prevents learning

- Reinforces errors

- Hinders scientific progress

Scientific solution

- Actively seek disconfirming evidence

- Report all results (positive and negative)

- Pre-register analysis plans

2. Ad Hominem (Attack the Person)

What it is

- Attacking the person instead of their argument

- Using personal insults instead of logic

- Mudslinging

Examples

❌ "You can't trust their climate research—they're a leftist!"

❌ "His statistics are wrong because he's funded by Big Pharma!"

❌ "She's just saying that because she's young and naive."

What’s wrong

- Person’s character ≠ argument’s validity

- Deflects from actual issues

- Prevents rational discussion

Correct approach

"Their climate model has these specific flaws: [list flaws]"

"The statistics use an inappropriate test because [explain]"

"Her argument overlooks this evidence: [cite evidence]"

3. Appeal to Authority

What it is

- Citing authority as justification

- Without explaining their evidence or reasoning

Not always a fallacy

"Einstein showed E=mc² through these equations..." (cites work)

"According to Smith et al. (2020), [summarizes findings]" (explains study)

Is a fallacy

❌ "Einstein said it, so it must be true!" (person, not evidence)

❌ "Dr. X claims Y works, and he's an expert!" (authority, not data)

Key distinction

- Authority’s research = evidence ✓

- Authority’s opinion = not evidence ✗

4. Straw Man

What it is

- Misrepresenting opponent’s position

- Making it easier to attack

- Defeating weak version instead of actual argument

Example

Person A: "We should have some gun regulations to reduce violence."

Person B: "You want to ban all guns and leave people defenseless

against criminals! That's absurd!"

[Person A never said "ban all guns"—that's a straw man]

Why it’s called “straw man”

- Straw man = easy to knock down

- Like fighting a scarecrow instead of real opponent

- Creates appearance of winning without addressing real argument

How to avoid

- Accurately represent opponent’s actual position

- Ask for clarification if uncertain

- Address strongest version of argument

5. Argument from Ignorance

What it is

- Claiming something is true because it hasn’t been proven false

- Or vice versa

Examples

❌ "No one has proven aliens don't exist, so they must be real!"

❌ "Science can't explain consciousness, therefore it must be supernatural!"

❌ "We don't know how the universe began, so God must have created it!"

Why it’s wrong

- Lack of evidence ≠ evidence of absence

- Burden of proof on person making claim

- Many things unknown—doesn’t make all explanations equally valid

Correct reasoning

"We don't have evidence for aliens, so we should remain agnostic."

"We don't fully understand consciousness, so we need more research."

"Multiple hypotheses about universe's origin remain scientifically viable."

6. False Dichotomy (False Dilemma)

What it is

- Presenting only two options

- When actually more exist

- Usually presenting extremes

Examples

❌ "America: Love it or leave it!"

❌ "You're either with us or against us!"

❌ "Either we cut all social programs or the economy collapses!"

Why it’s manipulative

- Polarizes discussion

- Eliminates middle ground

- Forces choice between extremes

- Obscures nuanced solutions

Reality

Middle positions exist

Partial solutions possible

Compromise feasible

Multiple options available

7. Slippery Slope

What it is

- Claiming one action inevitably leads to extreme consequences

- Without evidence for the causal chain

- Each step supposedly leads inexorably to next

Examples

❌ "If we allow gay marriage, next people will marry animals!"

❌ "If we ban one gun, soon they'll ban all guns!"

❌ "If I don't go to this party, I'll have no friends, fail school,

and end up homeless!"

When it’s legitimate

- If evidence supports each step in chain

- If mechanism for progression is demonstrated

- If historical precedent exists

When it’s a fallacy

- No evidence for progression

- Jumps to extreme without justification

- Uses fear instead of logic

8. Circular Argument (Begging the Question)

What it is

- Conclusion is hidden in the premise

- Assumes what you’re trying to prove

- Argument repeats itself

Examples

❌ "The Bible is true because it says so in the Bible."

❌ "I'm trustworthy because I say I'm trustworthy."

❌ "This law is good because it promotes good values."

[What makes the values good?]

Why it fails

- Doesn’t actually prove anything

- Just restates assumption

- No new information added

Valid argument structure

Independent premises → Conclusion

Evidence → Inference

Data → Interpretation

9. Red Herring

What it is

- Introducing irrelevant information

- To distract from real issue

- Shifting focus to easier/safer topic

Example

Journalist: "Why did the government waste millions on this failed project?"

Politician: "Let me tell you about all the great schools we've built!

Education is so important, don't you agree?"

[Didn't answer question about waste—introduced different topic]

Why it works

- People follow new conversational direction

- Original question forgotten

- Difficult topic avoided

How to counter

- Recognize the shift

- Return to original question

- Don’t follow the distraction

10. Sunk Cost Fallacy

What it is

- Continuing because of already invested resources

- Even when additional costs outweigh benefits

- “Can’t waste what I’ve already put in!”

Examples

❌ "I've watched 5 seasons of this show—I have to finish it!"

[Even though you're not enjoying it]

❌ "I've already spent $500 fixing this car—I should keep fixing it!"

[Even though it needs $2000 more and is worth $1000]

❌ "We've invested 5 years in this relationship—can't give up now!"

[Even though both people are miserable]

Why it’s irrational

- Past costs are gone (sunk)

- Should only consider future costs vs. benefits

- Past investment is irrelevant to future decisions

Rational approach

Evaluate: Future costs vs. Future benefits

Ignore: Past costs (already gone)

Ask: "If I were starting fresh, would I begin this?"

Testing Your Understanding

Wason Selection Task

The Setup

You see four cards with letters on one side, numbers on the other:

| Card 1 | Card 2 | Card 3 | Card 4 |

| A | K | 2 | 7 |

The Rule “If vowel on one side, then even number on other side”

Which card(s) must you turn over to test whether the rule is true?

Think carefully before reading on!

Most common answer Cards 1 (A) and 3 (2)

This is WRONG!

Correct answer Cards 1 (A) and 4 (7)

Why?

Card 1 (A)

- ✅ Must check: Vowel, so must have even number

- If odd number on back → rule is false

Card 2 (K)

- ✗ No need to check: Consonant

- Rule says nothing about consonants

- Could have even or odd—both OK

Card 3 (2)

- ✗ No need to check: Even number

- Rule says nothing about what’s on other side of even numbers

- Could have vowel or consonant—both OK

Card 4 (7)

- ✅ Must check: Odd number

- If vowel on back → rule is false

- (Rule says vowels must have even numbers)

What this demonstrates

Confirmation bias!

People test cases that could confirm the rule (vowel, even number)

…instead of cases that could falsify it (vowel?, odd number)

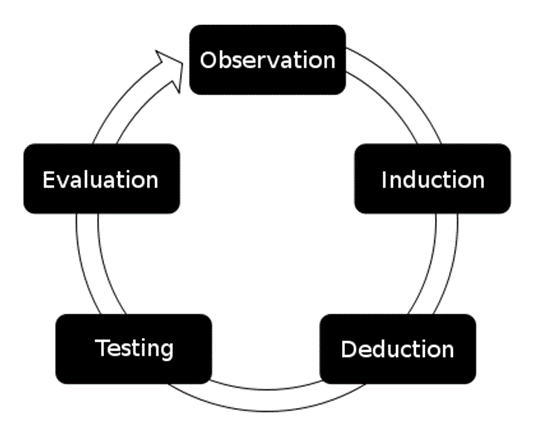

Scientific thinking requires

- Testing what could prove you wrong

- Not just seeking confirmation

- Actively trying to falsify

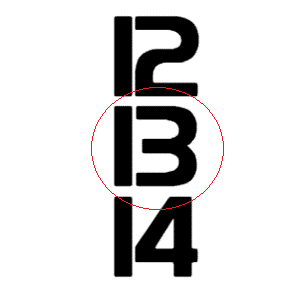

Number Sequence Puzzle

I have a rule for generating numbers. Here are three numbers following my rule

| Number 1 | Number 2 | Number 3 | Number 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | ? |

You can propose one number, and I’ll tell you if it follows my rule.

What number would you propose?

What rule do you think I have in mind?

Typical responses

First guess 8

Proposed rule “Double the previous number”

My response Yes, 8 follows my rule!

But This is NOT my rule!

Second guess 16

Proposed rule “Square the previous number”

My response Yes, 16 follows my rule!

But This is STILL NOT my rule!

Better approach

Test numbers that would disconfirm your hypothesis

- Try 3 (doesn’t fit doubling rule)

- Try 7 (doesn’t fit doubling rule)

- Try 10 (doesn’t fit doubling rule)

My actual rule “Each number must be larger than the previous”

What this demonstrates

Confirmation bias again!

People propose numbers that confirm their hypothesis

…instead of numbers that would falsify it

Science requires

- Testing what would prove you wrong

- Challenging your own ideas

- Seeking disconfirming evidence